Canadiens Hall of Fame defenseman was born on this day in 1928

Long before Guy Lafleur wore No. 10 for the Montreal Canadiens, a lesser-known Canadiens Hall-of-Fame defenseman quietly patrolled the blueline with the same number.

"When I first came up we would play a lot of exhibition games all around Quebec, even during the season. They would introduce the players in the order of their numbers, and of course Rocket was number nine,” said the late Tom Johnson in Dick Irvin’s book “The Habs”.

“The cheer he got would last a long time. I always say I used to skate out at the end of the Rocket's cheer. They could never hear my name, so not too many people in those towns ever found out who I was."

While many always remember Doug Harvey as “THE” defenseman of his era during the ‘50s and ‘60s, Tom Johnson was certainly no second banana. Though as not as fast a skater as his counterpart, Johnson made up for it with his excellent stickhandling, passing abilities and defensive play.

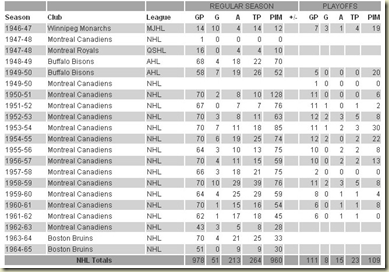

A standout junior player in his native Manitoba, Johnson was signed as a free agent by Canadiens GM Frank Selke in 1947.

He got his first taste of the NHL in the 1947-48 season, playing just a single game.

His debut was not a memorable one as fans, and even coach Dick Irvin, questioned Selke’s prospect, noting his poor skating abilities.

With the likes of Harvey, Emile Bouchard, Hal Laycoe, and Ken Reardon already in place on the Canadiens roster, it would take three seasons in the minors for Johnson to earn his spot.

Johnson worked hard with the Montreal Royals and Buffalo Bisons and once he finally cracked the roster to start the 1950-51 season, he’d be there to stay for the next thirteen.

“Irvin is the steadiest defenceman in the league today,” Irvin said during Johnson’s first full season. “He’s one of the reason’s we’re still in the battle. And what’s more, he’s a future All-Star.”

An All-Star he truly would be, as he played in eight All-Star games, and was named as a First-Team All Star in 1959 and a Second Team All-Star in 1956.

Many would say that anyone paired on the blue line with Doug Harvey would flourish, but Johnson was not just any player.

“I was classified as a defensive defenceman. I stayed back and minded the store,” Johnson said. “With the high powered scoring teams I was with, I just had to get them the puck and let them do the rest.”

In light of being in the shadow of his teammate, Johnson’s near flawless stay at home play gave Harvey and the rest of the Canadiens the added defensive conscience to carry the puck up ice on an offensive charge.

''Of all the great players I covered in Montreal in the 1950s, I don't think there was anybody who played with more pain when he had to,'' said legendary Canadiens reporter Red Fisher on Johnson’s durability.

''He'd take shots in his knees. They were ripped up, and he'd come out and play. Injuries didn't matter to this guy. He'd never make any kind of a big deal about it. This guy came out and played like no other player did. I admired him a great deal for it.' ”

He proved just how good he was in the 1958-59 season. With the perennial Norris trophy winner Harvey injured during part of the season, Johnson carried on in his absence, and won the Norris for his efforts.

Johnson appeared on this Feb ‘58 SI cover alongside Jacques Plante

There was also a bit of a dirty side to Johnson’s play as he had a reputation, and dislike from many opponents, for using his stick in scuffles.

Johnson played on seven Stanley Cup winning teams with Montreal, including their five consecutive Cups from 1956 to 1960.

His tenure in Montreal would come to an end during a team practice in March 1963 when Johnson collided with rookie Bobby Rousseau, fracturing his cheekbone and injuring his eye. He would not return for the rest of the season.

In a summer that saw teammates Jacques Plante, Don Marshall and Phil Goyette traded to the New York Rangers, and unsure whether he would recover from his injury to play again, the Canadiens opted to leave Johnson unprotected in the off-season waiver draft.

“We figured Tom was a good gamble,” said Bruins GM Lynn Patrick, who had suffered and recovered from a similar injury. "

“Naturally I regret leaving the Canadiens. After all I was there for 13 years,” Johnson said. “But I’m glad of the opportunity to play in Boston. I think I’ll like it there.”

Like it he would as it would turn into a 30-year relationship between Johnson and the Bruins.

In his second season with the Bruins, on February 28 1965, the skate of Chicago Blackhawks Chico Maki severed the nerves in his leg. Johnson was forced to retire as a player, but stayed on with the Bruins front office as an assistant GM.

The Bruins won the Stanley Cup in 1970, and Johnson was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in the same year, despite apparent protests on his dirty playing style for fellow member Eddie Shore.

He took over as the Bruins head coach in June of 1970. Johnson now found himself coaching the man who was in the process of surpassing his former teammate as the game’s greatest blueliner, Bobby Orr.

After seeing his team ousted by the Canadiens, and a kid named Dryden, in the ‘71 playoffs, Johnson’s team won the Cup back in 1972.

When the team got into a mini-slump the following season, despite a 31-16-5 record, Johnson was fired by GM Harry Sinden.

His career coaching win percentage of .738 (142-43-23) is the highest career winning percentage (min. 100 games) for any NHL coach.

He remained with the Bruins in his assistant-GM position and later became vice-president of the team. Through the late ‘70s, Johnson had his scouts keep tabs on a young midget and junior player named Raymond Bourque.

Sadly Tom Johnson died of heart failure, at age 79, on November 21, 2007.

"If we are all allowed an ultimate friend, mentor, confidant and teacher, Tom Johnson was all of those to me," said Sinden. "The Bruins and all of hockey have lost a great person."

No comments:

Post a Comment